John Hoyland: The Last Paintings

Saturday 3 July – Sunday 10 October at

Millennium Gallery, Sheffield S1 2PP

Below the Press, I talk to Sam Cornish, a representative from the John Hoyland estate - best pp

The John Hoyland Estate, in partnership with Sheffield Museums, is pleased to announce the exhibition John Hoyland: The Last Paintings at Millennium Gallery, Sheffield opening July 2021. This exhibition will focus on the series of paintings made in the last years of Hoyland’s life; an exuberant celebration of a life well-lived and a meditation on its approaching end.

One of Britain’s leading abstract painters, John Hoyland is renowned for his bold use of colour and inventive forms. His tireless innovation pushed the boundaries of abstract painting and cemented him as one of the most inventive British artists of the 20th century.

The Last Paintings will display works made in the last eight years of Hoyland’s life, showing previously unseen paintings, such as Moon In The Water, the last of Hoyland’s Mysteries series, for the first time. The paintings celebrate life in the face of death, as Hoyland reckoned with the deaths of his friends and faced down his own mortality. He uses semi-figurative language to confront this, centring images of the void and the cosmos, suns, moons, stars, and occasionally birds and figures.

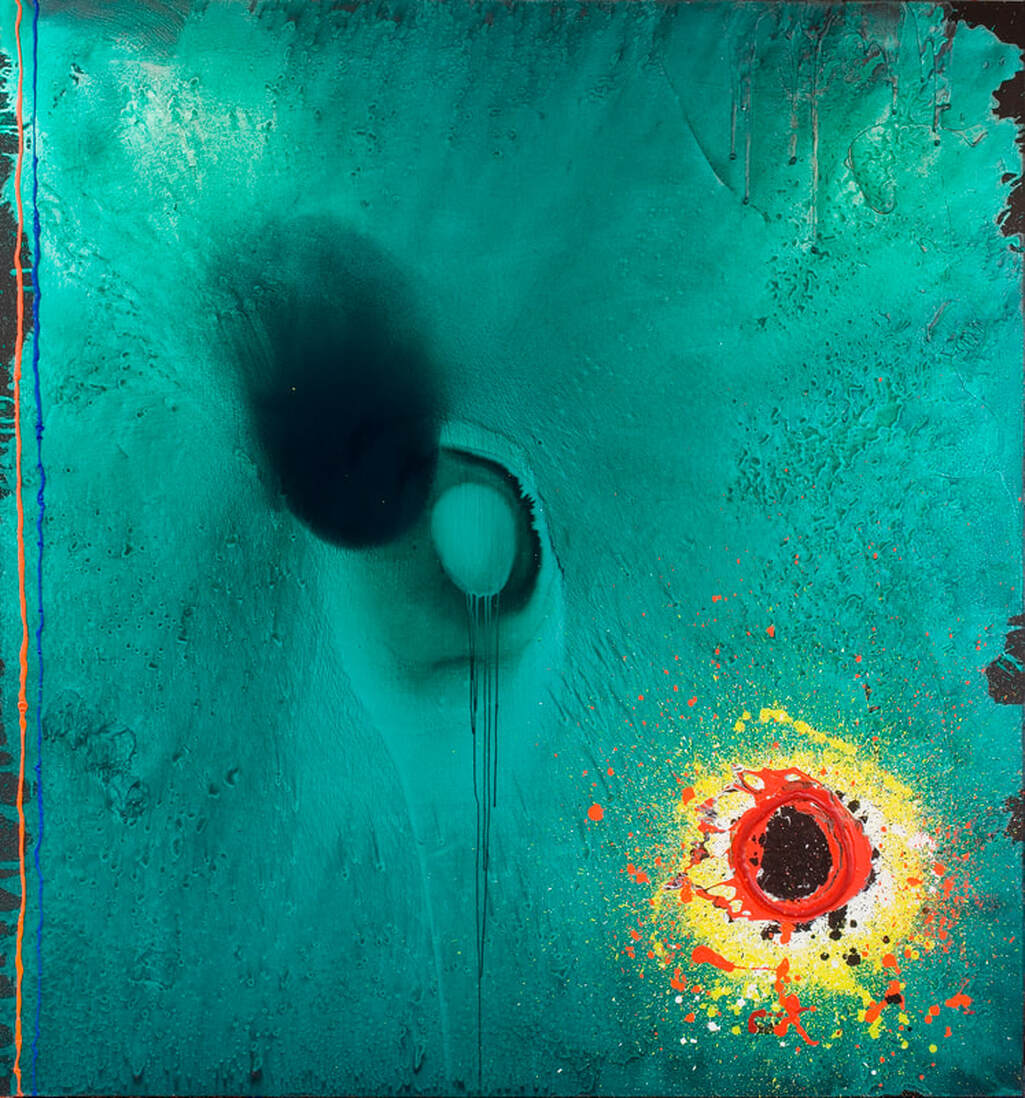

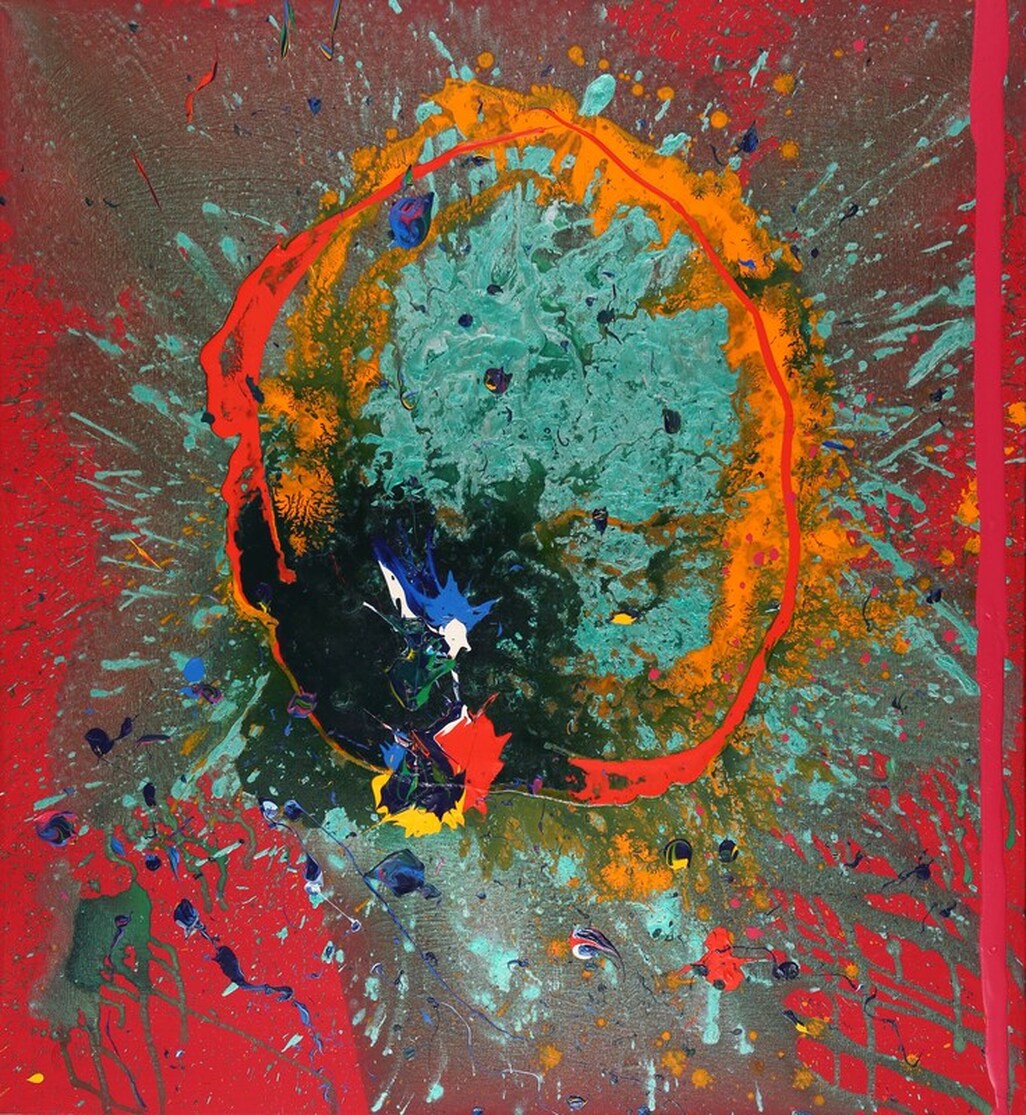

This final series of paintings pays homage to some of his artistic heroes, such as Vincent Van Gogh in Night Sky, as well as commemorating artist-friends in Elegy (for Terry Frost), which uses colour to allude to Frost’s art, with its red, yellow, black and white roundel set against a deep emerald redolent of the sea near Frost’s home in St Ives. Restless Heart is a statement of Hoyland’s passionate commitment to life and love, and a defiant acknowledgement of his declining health. Leaving hospital in 2008 after major heart surgery, he felt ‘a distinct sharpening of the senses.’ Although illness shortened Hoyland’s life, it simultaneously produced a late burst of creative energy.

"by far the greatest British abstract painter ... John Hoyland was an artist who was never afraid to push the boundaries. His paintings always feel like a massive celebration of life to me." : Damien Hirst

Elegy (For Terry Frost), 2003, 100 x 93 inches Painter Terry Frost was a close friend of Hoyland, who died in 2003. Hoyland’s majestic tribute to Frost includes a swirling roundel of yellow, red and black, a reference to Frost’s signature colours and motifs. Mel Gooding suggests in The Last Paintings book that the emerald green of the picture also refers to the colour of the sea outside Frost’s home in St Ives.

To commemorate the 10th anniversary of Hoyland’s passing, the exhibition will take place at the Millennium Gallery in his hometown of Sheffield, where his passion for art was first ignited. Born in 1934, Hoyland attended Sheffield School of Arts and Crafts, then went on to study Fine Art at Sheffield College of Art. Together with fellow pupil Brian Fielding, one of Hoyland’s closest friends and later a formidable artist in his own right, they rambled around post-war Sheffield discussing ‘art with a capital A’.

Leaving Sheffield in 1956 with little knowledge of contemporary abstract art, he quickly became swept up in a period of great artistic change. Hoyland’s knowledge of modern European art was joined to a love of American Abstract Expressionism, leading him to exhibit a series of abstract paintings for his diploma show in 1960. These works so shocked the then-president of the RA, Sir Charles Wheeler, that they were ordered down from the walls.

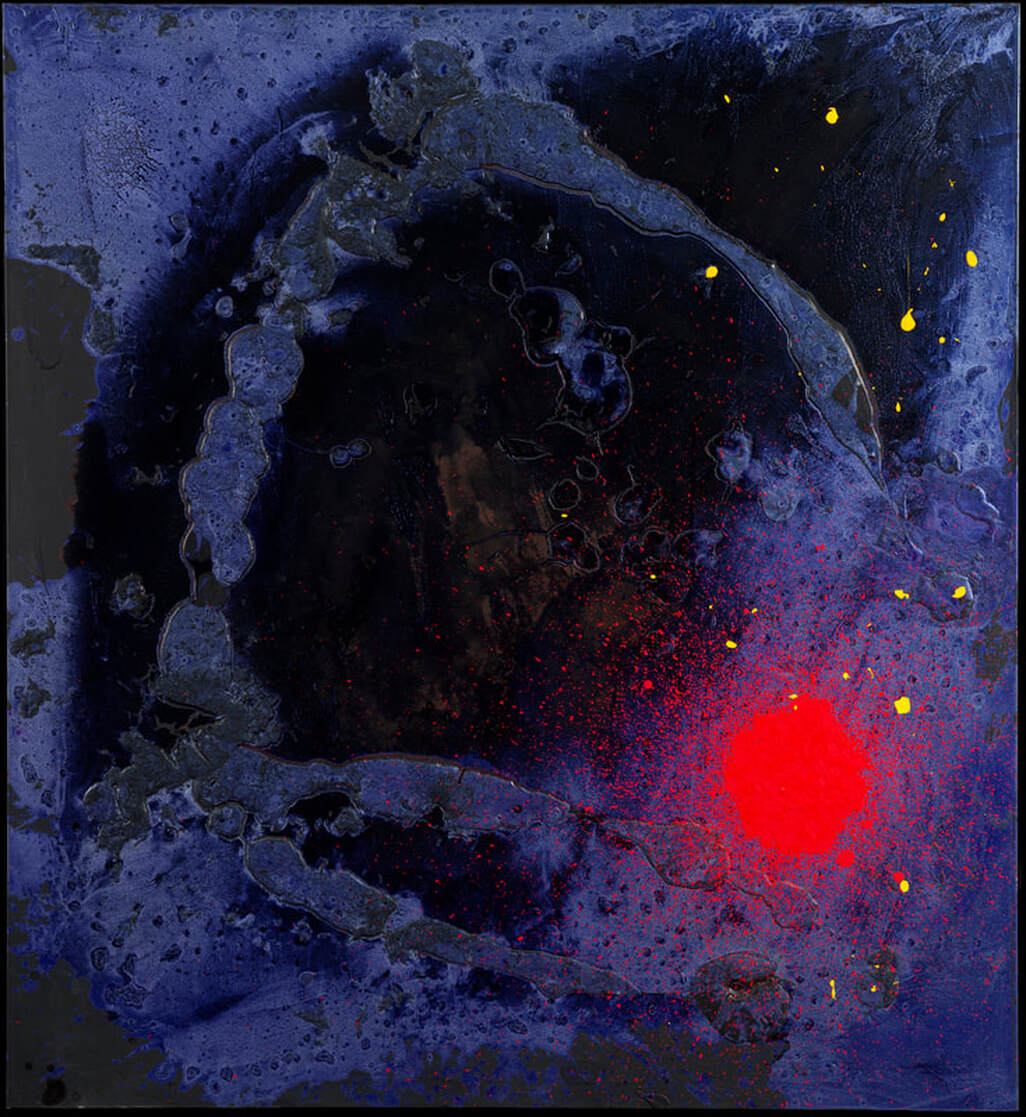

Moon In The Water (Mysteries), 2011, 60 x 55 inches Moon In The Water was Hoyland’s final painting and the last of the ‘Mysteries’, completed in April 2011, three months before his death. Its title appears to have been taken from a death-poem by the nineteenth-century Japanese Zen master Gizan, published in a book Hoyland owned by poet and promoter of Zen, Lucien Stryk. Coming and going, life and death: A thousand hamlets, a million houses. Don’t you get the point? Moon in the water, blossom in the sky. There is a readily appreciable if ultimately unfathomable connection between Gizan’s words and Hoyland’s image. Yet the succeeding phrase – ‘blossom in the sky’ – has the potential for an even more direct link with Hoyland’s late works, well describing their garlands of multicoloured marks dancing against intergalactic voids. The shining quiet of Hoyland’s last painting leaves these final words of Gizan’s poem poignantly unsaid. Last Paintings is the first time Moon In The Water will be exhibited.

By the mid-60s Hoyland had met many of the Abstract Expressionists, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Helen Frankenthaler; with Robert Motherwell becoming a life-long friend.

In 1960, Hoyland was included in the influential Situation group exhibitions and selected as one of Bryan Robertson's New Generation artists at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1964. His career went from strength to strength, opening his first institutional solo show in 1967 at the Whitechapel, where he presented a body of work critic Mel Gooding has referred to as 'an achievement in scale and energy, sharpness of definition and expressive power unmatched by any of his contemporaries, and unparalleled in modern British painting.’

Although Hoyland himself disliked the term abstraction, finding it smacked too much of geometry and rational thought, he was a life-long proponent of non-figurative imagery, in which he saw ‘the potential for the most advanced depth of feeling and meaning’. He believed that ‘...paintings are there to be experienced, they are events.’ His dramatic, colourful canvases are a testament to that belief, from the playful biomorphic forms of his early works to the expressive impasto acrylic of his later paintings.

In the last couple of decades his method involved laying down a dark ground with a paintbrush, on top of which he’d skate glazes of iridescent paint. Working on the floor, he’d spill, pour, squeeze and squirt liquid acrylic from an army of bottles. The critic Andrew Lambirth described this method rather aptly as ‘collaborating with chaos’: as Hoyland told him in a 2008 interview, ‘I like to try and make these pictures paint themselves. The less you impose, the fresher it is. Painting is a kind of alchemy.’

Restless Heart, 2008, 60 x 55 inches Hoyland had major heart surgery in 2008. Leaving hospital after 6 weeks he described feeling ‘a distinct sharpening of the senses’, which led to a burst of creative energy. Restless Heart is one of a number of paintings from this time that refer to his ill-health. Others in this group include a motif based upon his long, jagged surgical scar. The mood of these works, although never without a hint of darkness, and sometimes of melancholy, is defiant and celebratory. Hoyland was not interested in feeling sorry for himself! ‘Heart’ should also be understood as a symbol of a lifelived passionately, by an artist dedicated to an art of feeling above all else.

The defiant energy and joy of the works, with stormy indigo washes punctuated by vibrant red dashes, speak to Hoyland’s rebellious approach to life. Damien Hirst has said of Hoyland ‘...by far the greatest British abstract painter ... John Hoyland was an artist who was never afraid to push the boundaries. His paintings always feel like a massive celebration of life to me.’

A new book published by Ridinghouse which surveys Hoyland’s final series of paintings will be released in Summer 2021.

John Hoyland: The Last Paintings opens at Millennium Gallery

on Saturday 3 July and continues until Sunday 10 October – entry to the exhibition is free.

Twitter: @HoylandStudio / @SheffMuseums

Instagram: @johnhoylandra / @SheffMuseums

Facebook: @SheffieldMuseums

on Saturday 3 July and continues until Sunday 10 October – entry to the exhibition is free.

Twitter: @HoylandStudio / @SheffMuseums

Instagram: @johnhoylandra / @SheffMuseums

Facebook: @SheffieldMuseums

Hello Sam, thanks for talking to us, firstly, what were the main influences on Hoyland’s final paintings?

Hoyland's last paintings were the culmination of more than half a century of making and looking at art, and of living. It's hard to completely separate out which influences on these paintings were most important, from the French painter Nicolas de Stael to Abstract Expressionism. But in a number of his last paintings he paid tribute to deceased contemporaries - including the artists Terry Frost, Patrick Caulfield and Piero Dorazio - and to illustrious predecessors. Most important of these were Vincent van Gogh to whom Hoyland dedicated about a dozen paintings, including Night Sky (2005) that will be shown in the Millennium Gallery exhibition in Sheffield this summer. Hoyland had major heart surgery in 2008 and his last paintings - especially the final series, The Mysteries - also see him facing his own mortality.

What or who were Hoyland’s main creative inspirations?

It is hard to do better than a list Hoyland himself first made in the 1980s (this version from 1995):

"Finally, what is the subject of my work? I can only hazard a guess, a list of things: masks, mirrors, Avebury stone circle viewed from the air, mountains, waterfalls, graffiti, damp walls, cracked pavements, the cosmos, tropical fruit, drink, music, tropical light, oceanic light, Mediterranean light, tribal art, Indian, Japanese and Chinese art, drums, jazz, African Highlife music, reggae, soul, Latin and classical, modern dance, magic realism, Borges, the metaphysical, dawn, sunset, atolls, flowers, The Book of Imaginary Beings, The Directory of Angels, Bangkok, Rio de Janeiro, Montego Bay and Bali… All to create a sense of magic – trying to transform the commonplace into the real to make paradise."

What artistic training did Hoyland receive?

At the age of eleven, Hoyland began studying at the Sheffield School of Art & Crafts (junior department), and then the Sheffield College of Art, between 1951 and 1956. He moved to London in 1956 and spent four years at the Royal Academy Schools. In 1957 he attended a summer school in Scarborough taught by artists Victor Pasmore, Harry Thurbon and Tom Hudson. This was an important introduction in how to understand and create abstract structure.

Did Hoyland think that formal training was important for an artist?

As he himself put it in 2001:

"Art is craft, but sometimes it miraculously crosses over into Art. Frans Hals was a wonderful painter, but he wasn’t Rembrandt and we don’t know why.

By merely painting an idea, or having an idea painted, the central act of creativity is removed; that is, the things one discovers in the physical process of making the work, together with the intuitive decisions made along the way, and, of course, a bit of luck."

Did Hoyland want to pursue art from an early age?

Late in life Hoyland remembered that his mother Kathleen encouraged him towards art, she would only let him stay up late in the evening if he was drawing, so this quickly encouraged him into regular practice. Hoyland remained close to his mother for his whole life, and she survived him by only a matter of weeks.

What impact did Hoyland have on British abstract painting?

For many years Hoyland was a central figure in British abstract painting, although his influence certainly waned in the later years of his career. We think his later work, from the 80s, 90s, and 2000s, is overdue for serious reassessment and that its impact is yet to be felt.

Thank you Sam Cornish

Hoyland's last paintings were the culmination of more than half a century of making and looking at art, and of living. It's hard to completely separate out which influences on these paintings were most important, from the French painter Nicolas de Stael to Abstract Expressionism. But in a number of his last paintings he paid tribute to deceased contemporaries - including the artists Terry Frost, Patrick Caulfield and Piero Dorazio - and to illustrious predecessors. Most important of these were Vincent van Gogh to whom Hoyland dedicated about a dozen paintings, including Night Sky (2005) that will be shown in the Millennium Gallery exhibition in Sheffield this summer. Hoyland had major heart surgery in 2008 and his last paintings - especially the final series, The Mysteries - also see him facing his own mortality.

What or who were Hoyland’s main creative inspirations?

It is hard to do better than a list Hoyland himself first made in the 1980s (this version from 1995):

"Finally, what is the subject of my work? I can only hazard a guess, a list of things: masks, mirrors, Avebury stone circle viewed from the air, mountains, waterfalls, graffiti, damp walls, cracked pavements, the cosmos, tropical fruit, drink, music, tropical light, oceanic light, Mediterranean light, tribal art, Indian, Japanese and Chinese art, drums, jazz, African Highlife music, reggae, soul, Latin and classical, modern dance, magic realism, Borges, the metaphysical, dawn, sunset, atolls, flowers, The Book of Imaginary Beings, The Directory of Angels, Bangkok, Rio de Janeiro, Montego Bay and Bali… All to create a sense of magic – trying to transform the commonplace into the real to make paradise."

What artistic training did Hoyland receive?

At the age of eleven, Hoyland began studying at the Sheffield School of Art & Crafts (junior department), and then the Sheffield College of Art, between 1951 and 1956. He moved to London in 1956 and spent four years at the Royal Academy Schools. In 1957 he attended a summer school in Scarborough taught by artists Victor Pasmore, Harry Thurbon and Tom Hudson. This was an important introduction in how to understand and create abstract structure.

Did Hoyland think that formal training was important for an artist?

As he himself put it in 2001:

"Art is craft, but sometimes it miraculously crosses over into Art. Frans Hals was a wonderful painter, but he wasn’t Rembrandt and we don’t know why.

By merely painting an idea, or having an idea painted, the central act of creativity is removed; that is, the things one discovers in the physical process of making the work, together with the intuitive decisions made along the way, and, of course, a bit of luck."

Did Hoyland want to pursue art from an early age?

Late in life Hoyland remembered that his mother Kathleen encouraged him towards art, she would only let him stay up late in the evening if he was drawing, so this quickly encouraged him into regular practice. Hoyland remained close to his mother for his whole life, and she survived him by only a matter of weeks.

What impact did Hoyland have on British abstract painting?

For many years Hoyland was a central figure in British abstract painting, although his influence certainly waned in the later years of his career. We think his later work, from the 80s, 90s, and 2000s, is overdue for serious reassessment and that its impact is yet to be felt.

Thank you Sam Cornish

John Hoyland: The Last Paintings

Saturday 3 July – Sunday 10 October

Location: Millennium Gallery, Arundel Gate, Sheffield, S1 2PP

Millennium Gallery is open Tuesday - Friday 10am - 4pm, Sunday 11am - 4pm

Saturday 3 July – Sunday 10 October

Location: Millennium Gallery, Arundel Gate, Sheffield, S1 2PP

Millennium Gallery is open Tuesday - Friday 10am - 4pm, Sunday 11am - 4pm

share

|

|

|