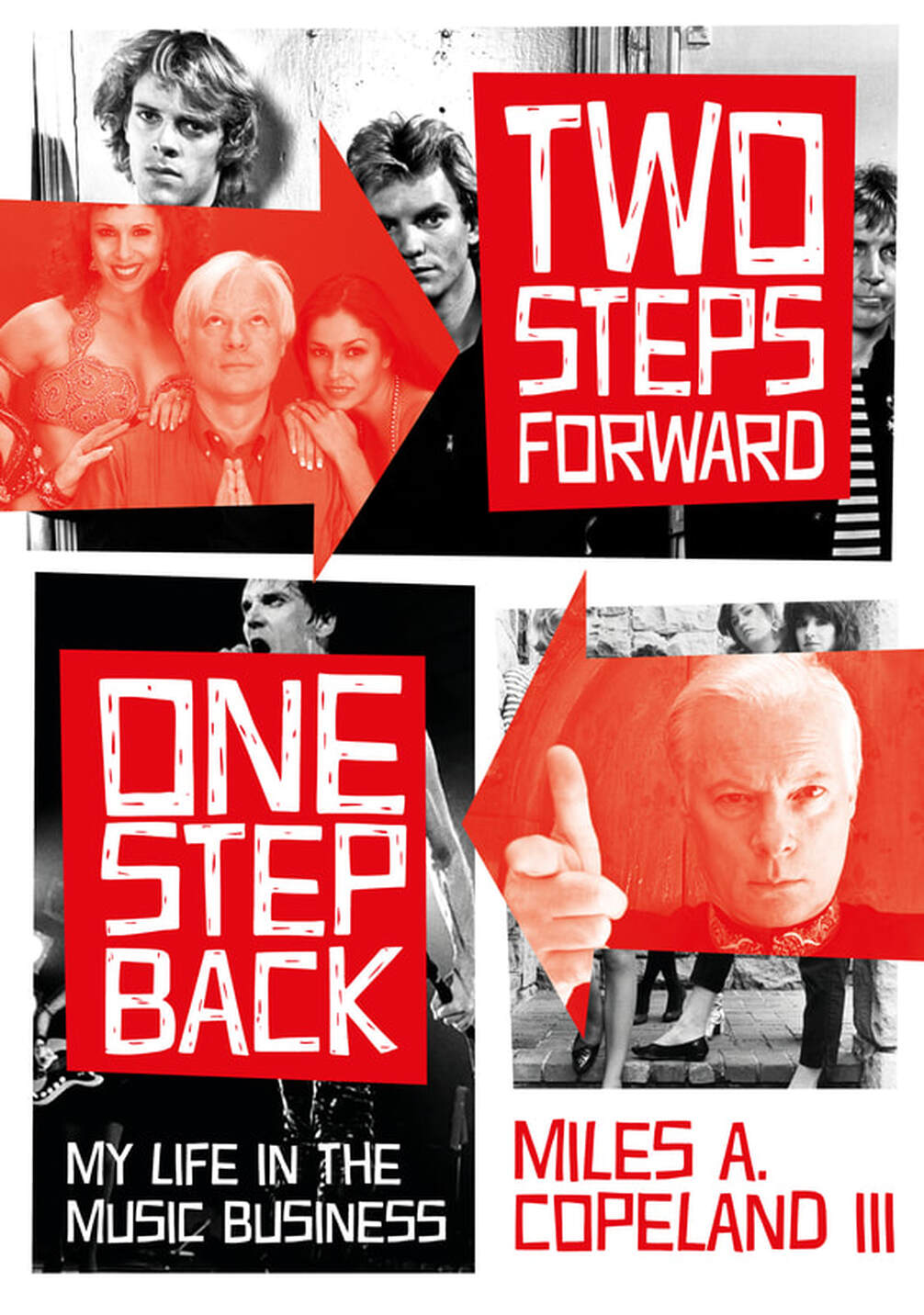

MILES A. COPELAND III

'TWO STEPS FORWARD, ONE STEP BACK

MY LIFE IN THE MUSIC BUSINESS'

Memoirs of a music-industry maverick. Published June 18th by Jawbone Press.

“This refreshing and provocative book will surprise, shock, and inform both music-business insiders and civilians on the fringes of showbusiness. It is an essential read for anyone considering a career in the music industry.” Jools Holland

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back tells the extraordinary story of a maverick manager, promoter, label owner, and all-round legend of the music industry. It opens in the Middle East, where Miles grew up with his father, a CIA agent who was stationed in Syria, Egypt, and Lebanon. It then shifts to London in the late 60s and the beginnings of a career managing bands like Wishbone Ash and Curved Air—only for Miles’s life and work to be turned upside down by a disastrous European tour.

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back tells the extraordinary story of a maverick manager, promoter, label owner, and all-round legend of the music industry. It opens in the Middle East, where Miles grew up with his father, a CIA agent who was stationed in Syria, Egypt, and Lebanon. It then shifts to London in the late 60s and the beginnings of a career managing bands like Wishbone Ash and Curved Air—only for Miles’s life and work to be turned upside down by a disastrous European tour.

“Miles was larger than life to our band, The Go-Go’s. We were in awe and a little bit afraid of him, but at the end of the day we considered him a protector, and we knew we could trust him...Berlinda Carlisle

From the ashes of near bankruptcy, Miles entered the world of punk, sharing a building with Malcolm McLaren and Sniffin’ Glue, before shifting gears again as manager of The Police, featuring his brother Stewart on drums. Then, after founding IRS Records, he launched the careers of some of the most potent musical acts of the new wave scene and beyond, from Squeeze and The Go-Go’s to The Bangles and R.E.M.

“Miles was larger than life to our band, The Go-Go’s. We were in awe and a little bit afraid of him, but at the end of the day we considered him a protector, and we knew we could trust him. He helped us navigate the early days of our career. He’s a legend!” Belinda Carlisle

The story comes full circle as Miles finds himself advising the Pentagon on how to win over hearts and minds in the Middle East and introducing Arabic music to the United States. ‘Never let the truth get in the way of a good story,’ his father would tell him. In the end, though, the truth is what counts—and it’s all here.

Miles Copeland

talks to Eoghan Lyng

What was the impetus for the book?

Well, I had all this time during lockdown, so I thought, “What am I going to do?” So, I decided to write a book.

What was it like growing up in the Middle East?

The major thing about it was , you recognised very clearly that you were not from there. You were an American. As an American, you assume, I guess the same as the British, or the French, or whatever, you assume that you were something different. You know, you had education, you had money, you were looked upon as something special, as opposed to the local people. So, in a way it was a sheltered environment, because you were only exposed to …[Pauses for thought.] I mean, you had chauffeurs and maids, and all that sort of stuff, which in America, we couldn’t have been able to afford. When you were in the Middle East, you lived a different lifestyle. You live a lifestyle like a rich person, basically.

And is Stewart Copeland the fourth in the family?

Stewart is the youngest of the four siblings: youngest of the three brothers. My sister is the “Second In Line”, basically. Then there was Ian, and then Stewart.

Your father was in the CIA, correct? He was originally in the OSS, which was the precursor to the CIA. It was stationed in London, where he met my mother, who was in British Intelligence, which was then known as SOE. When the war was over, he was then stationed in Washington D.C. to help centralise the various intelligence agencies that had grown up during the war. Hence, it was called the “Central Intelligence Agency”. So, he was one of the “Founding Fathers” of the CIA.

Did you say that your mother was British?

She was British, and in British Intelligence, which is why they met.

That clears up the next point: Both you and Stewart had prosperous careers in London. Was the family connection a draw?I

left Beirut in 1969, and went to London. My brother Stewart was still in school, and I had met a British group in Beirut, who came to see me when I was in London, and they said, “We think you should manage us”. [That] was a shock to me, because I knew nothing about music. Which, in a way, is part of what the book is about. When I wrote it, it was more of an inspirational , motivational book, as opposed to a memoir; “Writing about yourself.” And it really is about, “You don’t need to know so much, you just need the gumption to get up and do it.” When I arrived in London, I literally knew nothing. I went to Carnegie Street, and bought myself my first bell bottom trousers. I set about learning about the music business: I went around to the clubs, and bought the Melody Maker...I tried to learn what the business was all about, and learned by making mistakes, and having successes as well.

I read that Brian Epstein barely knew what he was doing when he first managed The Beatles. It was new territory for everybody.

Well, he at least had a record store company, so at least he knew about music, and record companies supplying in your store. I didn’t know about that. I always thought I was going to end up in the CIA, like my father, or have some sort of Middle Eastern business. I had no idea that I would be going into the music business. So, I had less tutelage than Brian Epstein did. But, like him, he was starting from scratch as a manager, which is what I did as well.

Can I ask how you got into contact with Wishbone Ash?

In the process of learning the music business, I went around to the clubs. One of the nights I went to a place, and I saw the group that became Wishbone Ash, and I met them on the night they were breaking up. They were called Tanglewood.So, I went up to the drummer, and I said,”I like what you’re doing..What’s your story?” He gave me a tale of woe about, “How the group is breaking up,”, so I said, “Maybe I can help!”They came to see me a couple days later, and I said, “Let’s look for a guitar player.” We reformed the group...And I guess they had nothing else to do, so they said, “What the hell!” Next thing I knew, I was the manager. We started doing auditions to try and find guitar players. We ended up with two guitar players; we couldn’t make up our minds! They were both lead guitarists, and we decided to take both of them. We ended up with Ted Turner, and Andy Powell.

On the subject of duelling guitars, was the two lead guitars format ever viable for The Police, or was Henri Padovani’s tenure always bound to be a short lived one?

I think what really happened there was that Henry [sic] looked great, and was very punky, and in the beginning The Police were very much trying to be a punk group. When Andy joined, he could play more than three chords. He was a pretty accomplished musician, and all of a sudden Sting realised that he could write songs that were a bit more complex. So, it didn’t really make a lot of sense to have two guitar players, one of whom at that point was not particularly well versed in the guitar. He later became a very good guitar player, I might add, and a good songwriter, but at that time he was not.

Pete Best has become a great drummer over the years, but people say he wasn’t up for it in 1962.

Yeah, people grow. Henry grew to become quite a famous person in France. He was one of judges on The X Factor!

Well, I had all this time during lockdown, so I thought, “What am I going to do?” So, I decided to write a book.

What was it like growing up in the Middle East?

The major thing about it was , you recognised very clearly that you were not from there. You were an American. As an American, you assume, I guess the same as the British, or the French, or whatever, you assume that you were something different. You know, you had education, you had money, you were looked upon as something special, as opposed to the local people. So, in a way it was a sheltered environment, because you were only exposed to …[Pauses for thought.] I mean, you had chauffeurs and maids, and all that sort of stuff, which in America, we couldn’t have been able to afford. When you were in the Middle East, you lived a different lifestyle. You live a lifestyle like a rich person, basically.

And is Stewart Copeland the fourth in the family?

Stewart is the youngest of the four siblings: youngest of the three brothers. My sister is the “Second In Line”, basically. Then there was Ian, and then Stewart.

Your father was in the CIA, correct? He was originally in the OSS, which was the precursor to the CIA. It was stationed in London, where he met my mother, who was in British Intelligence, which was then known as SOE. When the war was over, he was then stationed in Washington D.C. to help centralise the various intelligence agencies that had grown up during the war. Hence, it was called the “Central Intelligence Agency”. So, he was one of the “Founding Fathers” of the CIA.

Did you say that your mother was British?

She was British, and in British Intelligence, which is why they met.

That clears up the next point: Both you and Stewart had prosperous careers in London. Was the family connection a draw?I

left Beirut in 1969, and went to London. My brother Stewart was still in school, and I had met a British group in Beirut, who came to see me when I was in London, and they said, “We think you should manage us”. [That] was a shock to me, because I knew nothing about music. Which, in a way, is part of what the book is about. When I wrote it, it was more of an inspirational , motivational book, as opposed to a memoir; “Writing about yourself.” And it really is about, “You don’t need to know so much, you just need the gumption to get up and do it.” When I arrived in London, I literally knew nothing. I went to Carnegie Street, and bought myself my first bell bottom trousers. I set about learning about the music business: I went around to the clubs, and bought the Melody Maker...I tried to learn what the business was all about, and learned by making mistakes, and having successes as well.

I read that Brian Epstein barely knew what he was doing when he first managed The Beatles. It was new territory for everybody.

Well, he at least had a record store company, so at least he knew about music, and record companies supplying in your store. I didn’t know about that. I always thought I was going to end up in the CIA, like my father, or have some sort of Middle Eastern business. I had no idea that I would be going into the music business. So, I had less tutelage than Brian Epstein did. But, like him, he was starting from scratch as a manager, which is what I did as well.

Can I ask how you got into contact with Wishbone Ash?

In the process of learning the music business, I went around to the clubs. One of the nights I went to a place, and I saw the group that became Wishbone Ash, and I met them on the night they were breaking up. They were called Tanglewood.So, I went up to the drummer, and I said,”I like what you’re doing..What’s your story?” He gave me a tale of woe about, “How the group is breaking up,”, so I said, “Maybe I can help!”They came to see me a couple days later, and I said, “Let’s look for a guitar player.” We reformed the group...And I guess they had nothing else to do, so they said, “What the hell!” Next thing I knew, I was the manager. We started doing auditions to try and find guitar players. We ended up with two guitar players; we couldn’t make up our minds! They were both lead guitarists, and we decided to take both of them. We ended up with Ted Turner, and Andy Powell.

On the subject of duelling guitars, was the two lead guitars format ever viable for The Police, or was Henri Padovani’s tenure always bound to be a short lived one?

I think what really happened there was that Henry [sic] looked great, and was very punky, and in the beginning The Police were very much trying to be a punk group. When Andy joined, he could play more than three chords. He was a pretty accomplished musician, and all of a sudden Sting realised that he could write songs that were a bit more complex. So, it didn’t really make a lot of sense to have two guitar players, one of whom at that point was not particularly well versed in the guitar. He later became a very good guitar player, I might add, and a good songwriter, but at that time he was not.

Pete Best has become a great drummer over the years, but people say he wasn’t up for it in 1962.

Yeah, people grow. Henry grew to become quite a famous person in France. He was one of judges on The X Factor!

What was it like hearing ‘Roxanne’ for the first time?

I had gone into the studio: I thought I was going to be hearing a punk album. Stewart was all about making The Police a “Punk Group”, and I had expected to hear some work in the mode of angry, aggressive music. ‘Roxanne’ sort of stood out as...Very different. The group didn’t even want to play it to me, [because] they figured I was looking for punk music. ‘Roxanne’ didn’t fit. The engineer finally said, “I’m just going to play it anyway.” He put the song on, and the group kind of sat there, “We’re waiting for Miles to rip the song apart.” And at the end I said, “Gentlemen, you’ve written a classic!” And, “It’s too big for me, I’m going to issue you a big record deal.”They sat up; “What, you liked that?” I think that opened Sting’s eyes to the fact that he could write songs like that: ‘Can’t Stand Losing You’, ‘Message In A Bottle’. They were all lurking in the back of his mind, so I think me recognising ‘Roxanne’ as something special opened Sting’s mind as well.

He’s quite a profound lyricist. You worked on some of his early albums, correct?

I had gone into the studio: I thought I was going to be hearing a punk album. Stewart was all about making The Police a “Punk Group”, and I had expected to hear some work in the mode of angry, aggressive music. ‘Roxanne’ sort of stood out as...Very different. The group didn’t even want to play it to me, [because] they figured I was looking for punk music. ‘Roxanne’ didn’t fit. The engineer finally said, “I’m just going to play it anyway.” He put the song on, and the group kind of sat there, “We’re waiting for Miles to rip the song apart.” And at the end I said, “Gentlemen, you’ve written a classic!” And, “It’s too big for me, I’m going to issue you a big record deal.”They sat up; “What, you liked that?” I think that opened Sting’s eyes to the fact that he could write songs like that: ‘Can’t Stand Losing You’, ‘Message In A Bottle’. They were all lurking in the back of his mind, so I think me recognising ‘Roxanne’ as something special opened Sting’s mind as well.

He’s quite a profound lyricist. You worked on some of his early albums, correct?

I managed Sting for the first..What..Five to six albums? Up until 2001, basically. I worked on all The Police albums, then all the way with Sting until Brand New Day. He had the big hit with ‘Desert Rose’. He wrote it and sang it, and I brought in Cheb Mami, and came up with the Jaguar commercial which really exploded the song. I had to take some credit for that, but Sting wrote it and sang it, and it was a brilliant song that he wrote.

It’s a beautiful song. I think he put it on the Duets album which came out a couple of weeks ago.

It was a brilliant song. The funny thing was- and I tell this in the book- the powers that be at the record company refused to accept that song as a single. [The single] seemed obvious to me, because it had all the elements of a hit single. But they said, “Who is this Arab guy?” And, “He shouldn’t be singing the song at the beginning, because we don’t know his voice, so it’s not a single unless you take him off the record.” Then I’d ask them, “What’s your favourite song on the record?” They’d all say, “Desert Rose!” So, “Would you like the song if I took the Arab guy off?” They all said, “No!” Then, “Why are you telling me it’s not a single unless you take him off the record?!” So, it was one of those confusing moments, [that] “The Powers That Be in the Record Company” were looking at the rulebook, and not listening to the song. I was listening to the song, as was Sting, as was the people on the commercial when they finally heard it; they went out and bought it. The public knew more than the record people did!

As always!

It happens a lot! It also happened with The Bangles, and ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’. CBS told me it wasn’t a single, because it was too quirky. I had to bully them to get it released, and when it was released, it took off like a rocket! It became the number one single in the entire world. That just goes to show how even the experts can be wrong.

It had that indelible dance video. Did you work with Buzzcocks, the punk band?

The Buzzcocks were a very successful British punk group; one of the first. And they did very well in England, but they couldn’t any interest in America, like a lot of British groups of the time. The Americans tended to dismiss this, “Punk Phenomena”. I went to the group, and signed them for America. I put them on my label, which I created, called IRS Records. They were the first official release on IRS Records.

Did you work with Kevin & Lol from Godley & Creme?

Both of them were the guys who made The Police videos, so I knew them quite well. They were originally in 10cc, so they knew music, but they also knew visuals , so they were kind of an interesting marriage of music people and filmmakers. We used them to make a lot of The Police videos.

It’s a beautiful song. I think he put it on the Duets album which came out a couple of weeks ago.

It was a brilliant song. The funny thing was- and I tell this in the book- the powers that be at the record company refused to accept that song as a single. [The single] seemed obvious to me, because it had all the elements of a hit single. But they said, “Who is this Arab guy?” And, “He shouldn’t be singing the song at the beginning, because we don’t know his voice, so it’s not a single unless you take him off the record.” Then I’d ask them, “What’s your favourite song on the record?” They’d all say, “Desert Rose!” So, “Would you like the song if I took the Arab guy off?” They all said, “No!” Then, “Why are you telling me it’s not a single unless you take him off the record?!” So, it was one of those confusing moments, [that] “The Powers That Be in the Record Company” were looking at the rulebook, and not listening to the song. I was listening to the song, as was Sting, as was the people on the commercial when they finally heard it; they went out and bought it. The public knew more than the record people did!

As always!

It happens a lot! It also happened with The Bangles, and ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’. CBS told me it wasn’t a single, because it was too quirky. I had to bully them to get it released, and when it was released, it took off like a rocket! It became the number one single in the entire world. That just goes to show how even the experts can be wrong.

It had that indelible dance video. Did you work with Buzzcocks, the punk band?

The Buzzcocks were a very successful British punk group; one of the first. And they did very well in England, but they couldn’t any interest in America, like a lot of British groups of the time. The Americans tended to dismiss this, “Punk Phenomena”. I went to the group, and signed them for America. I put them on my label, which I created, called IRS Records. They were the first official release on IRS Records.

Did you work with Kevin & Lol from Godley & Creme?

Both of them were the guys who made The Police videos, so I knew them quite well. They were originally in 10cc, so they knew music, but they also knew visuals , so they were kind of an interesting marriage of music people and filmmakers. We used them to make a lot of The Police videos.

Kevin lives here in Ireland [sic], he lives in Dublin.

He sold me some of his gothic furniture!

Back to The Police: It’s been reported that the three guys experienced great tension. Was that stirred by the press?

I’ve learned my lesson. When I say to people, “It was highly exaggerated”, nobody really wants to hear that. Like MTV, they wanted that old saying: “When it bleeds, it leads.” The nastier something is, the better it is for the media. So, when I’d say, “Well, there are tensions, but there are tensions in every group..” I learned when I’d say such things, I would be cut out, like the MTV documentary. [Throws hands up in the air.] I’m hardly in it [chuckles.] I told them things that were the truth, but it wasn’t what they wanted to hear. So I would say, “Yes, The Police hated each other!” That makes a lot better press!

Oh dear!

The reality is, they were three guys on the make, who needed each other, but there was also tension. There was Stewart, who wanted the group to be [pauses to elaborate.] He formed the group, so they were sort of his group, yet Sting wrote the hits! So, they were sort of Sting’s group too. There was a tension, but I think the press did pan the flames a bit. A bit like they did with The Sex Pistols, for instance. So, I saw the press through the years, and it’s also one of the points in the book: Controversy leads to success. Just look at Donald Trump-would he have gotten so much press if he had been “Mr.Nice Guy?”

No, not at all.

Probably not!

That’s what Noel Gallagher said: He and Liam didn’t hate each other, but pretended to do so for the media.

I think there is a truth to that, and the more aggressive things seem, the better the press is. Like I say, “If it bleeds, it leads.”

You worked with The Go-Gos; what were they like?

To me, they had a winning formula: “Five Girls”, which immediately gets you a noteworthy press angle; they played their own instruments, and wrote their own songs; they were real and genuine… I thought, “How bad can it be?” I went for it… The very things that made me interested in the group were the things that turned off the major labels. The argument was: “They are all girls, and there has never been an all girl hit group!” So, they were turned down by every record company, and I.R.S Records, which never had a hit record, to me The Go-Go’s fit perfectly with our left of centre acts. They were left of centre, too, but they wrote really good songs. I brought in a producer who was well known as the songwriter, Richard Gottehrer. He actually honed the group into making an album that went to No.1, and it stands today as the only No.1 to hit the top of the Billboard Charts, by an all Girl Group. I mean, The Supremes had plenty of No.1 singles, but there wasn’t a group of all girls writing their own material, and playing it that had a No.1 album.

Did you work with Belinda Carlisle after she left the band?

Well, The Go-Go’s were in a way..First album goes to No.1. So, from there, you can only go down; in a way. By the third album, a lot of the tensions built in the group ...Charlotte Caffey, the songwriter, was making more money than the drummer...So, there were pressures, and they broke up. But we still had the individuals under contract, so we made a Belinda Carlisle solo album, which came out, and did very well. So, we carried on with Belinda. Then, we had a problem with the contracts, and we parted ways, but we remain very good friends, The Go-Go’s and I.

On “Leave Light On For Me”, the song features George Harrison performing a piercing guitar solo. Was that your decision?

I was not involved with that song, and helping to get George Harrison there. I got very involved with the artists, but not everything. I was signing artists who had integrity in of themselves, and they didn’t always need me interjecting my own thoughts. Whether it be ‘The Lords of The New Church’, who I wanted to call ‘The Lords of Discipline’, and they said’ No’. Was it my idea to put Stiv Bators and Brian James together? Yeah, but they made the music, and determined which way it would go. So, I would say, even in the case of The Police, some people credited me with a lot of the best of the ideas, but they were very open to ideas, which is what made them special. I had other groups that were equally talented, but that just were not open to ideas, and would reject things out of hand, or would worry that they were making a mistake. The Police were, “What the hell? Let’s try it!” I always thought that was a much better approach. It was sort of the same with Jools Holland: Jools was always very open to coming up with some crazy idea I had for him.

Wow.

When I talked him into being the host of The Police Special in Montserrat, he said, “If you think I can do it, I’ll do it!” Next thing you know, he’s an icon of the British media in England!

He’s royalty

I always worked best with artists who had integrity, but were open to ideas. And I think that’s really where I succeeded the best. Not every idea I came up with was a good one: The Police rejected ideas, so did Sting and Jools. But they listened, and were predisposed to say “yeah” if they thought it worked. I came up with enough ideas that did work, and in case of Sting, The Police and The Go-Go’s, it was an interesting marriage of convenience that worked.

Hugh Padgham, who worked with The Police, ended up becoming one of the “Go-to Producers” of the decade.

Hugh was a brilliant engineer: He could put down on tape exactly what the artist wanted. But, he really did depend on knowing what the artist wanted. He was not the kind who would interject, “You should do it this way.” For that reason, I always looked upon him more as an engineer than a producer. In fact, I convinced Sting out of stopping using him, because even when he knew Sting was making a mistake, he didn’t feel it was his place to tell him. I felt it was my place to tell him, but what I discovered on The Soul Cages album was that he had songs that I thought could have been hit singles if they’d been structured slightly differently. Hugh said, “Who am I to tell Sting how to write a song?” I thought that was his job!

Yeah!

Hugh didn’t see it that way, but he was a brilliant engineer. So, I have a lot of credit for Hugh Padgham, but I would not hire him to be a producer of a band that needed direction and help.

10cc’s Eric Stewart said the same about Padgham, when they worked together on Press to Play.

Yeah. I think the reason Sting had me as a manager is that he wanted somebody who would tell him the truth. So many artists really don’t want to hear the truth: They want you to tell them what they want to hear. I say this in the book, it’s one of the things if I look back on my career, I would probably have done better if I was a better liar. I actually signed a contract to manage Duran Duran-who I really liked. Great music, great videos, really nice people...I liked everything about them. I signed a management contract in 2000, or 2001; I’d just separated from Sting. I was free, and they had me listen to their songs. “Well, they’re good, but you’re gonna need that killer hit single.”

I see.

I don’t think that’s what they wanted to hear. Then they reformed the original five members, so they asked me what I thought I could get them as a record deal. I actually lied: I told them a figure which was four times higher than I thought I could get. Turned out, it wasn’t a bit enough lie!

Oh no!

They wanted it to be FIVE TIMES BIGGER! I said, “I can’t deliver what you’re expecting.” I sat there, tore up the contract in front of them, and I’ve never seen them since. There’s been other artists like that who thought that the job was to kick ass at the record company...Tell the record company what to do….The reality is, you can’t make people do something they know isn’t right. If I thought it was right, I’d be willing to kick their ass, but there were times when I knew that it wasn’t right….I’m just not that good a manager: I can’t make something happen that I don’t believe in myself!

Another similarity to Epstein was how frank he was: “Wear suits, not leather jackets.”

Yeah. Image is a lot more important than a lot of people give it credit for. I didn’t dream up The Police being three blond guys . It was a commercial that they did it for. When I saw it, I recognised that it was a unifying image that gave them a special look. I said, “Guys- that’s the look!” And I think that’s Kiss painting their faces, or The Beatles with long hair and suits. Look over history at Elvis Presley, and he definitely had a look that was different to everybody else. Lady Gaga, today!

True.

A lot of the acts, the image makes them standout. I was always very concerned with the music itself; the drive of the person or group; and, the image! And, when all those things clicked, you had a winner, and in the case of The Police, or The Go-Go’s, it clicked. You had a winner!

It’s interesting: I don’t think Soft Cell had an image..What were they like to work with?

I never worked with Soft Cell…

Not them, Soft Machine; Robert Wyatt and Soft Machine!

I never.. I worked with Andy Summers, but I didn’t work with Soft Machine. I’d seen them play live….They were not my kind of group, I would have said. They were the, sort of, epitome of “Progressive Rock”: “Put your head; don’t recognise the audience; thirty minute solos.” They were anything but punk, which was kind of surprising when Andy joined The Police having come from Soft Machine. The reality was that Andy hated punk, and Sting didn’t like punk either..The real punk fan was Stewart, but I think he was more interested in the stripped down, do-it-yourself energy than the music itself. A lot of those bands at the time really weren’t very good. They couldn’t play their instrument very well, and musically they were below par!

I agree!

The Police, however, could play!

John Bonham was in awe of Stewart’s drum style.

Stewart has been playing since aged twelve. He was a musician, as were Andy & Sting. They were three real musicians. They got caught up in the energy of the punk movement, which was exciting. They, in a sense, gravitated to the movement, without being crap musicians.

Have you any plans for a follow up book?

When you’re writing a book, one of the things that becomes apparent….I’ve been in the industry fifty years, so I’ve come across many artists, some who succeeded, and some who failed. There’s a lot of lessons in there..My approach was to put in the lessons , more than say, “This is what I did.” But I had to leave a lot of things out, because people didn’t know who Yip Yip Coyote was, for instance. I did leave some acts out, and had to cut the book down to be a reasonable length. So, when I first went with 400 pages, they looked at me, “Miles, more like 320!” I had one publisher who wanted less than that: Obviously, I can’t do that! What am I going to do, not mention The Bangles or The Go-Go’s? I ended up with a good compromise with a British Company, [who were] very open to making the length I thought it should be, and I signed with the British Company first. Then, I did an audible version for America, so I’ ve been thinking about doing another-maybe longer-book..Maybe, a limited edition that includes a lot of the things I left out. Because there were a lot of other bands that I really liked, but they might have broken up internally, or their manager was an idiot..Who knows? Any number of reasons: I, the band or the producer could have made a mistake. I think there’s a lot of lessons in some of those mistakes, and I would have loved to have included in the book. But, most of the things that are relevant are in the book.

Miles Copeland, thank you.

share

|

|

|