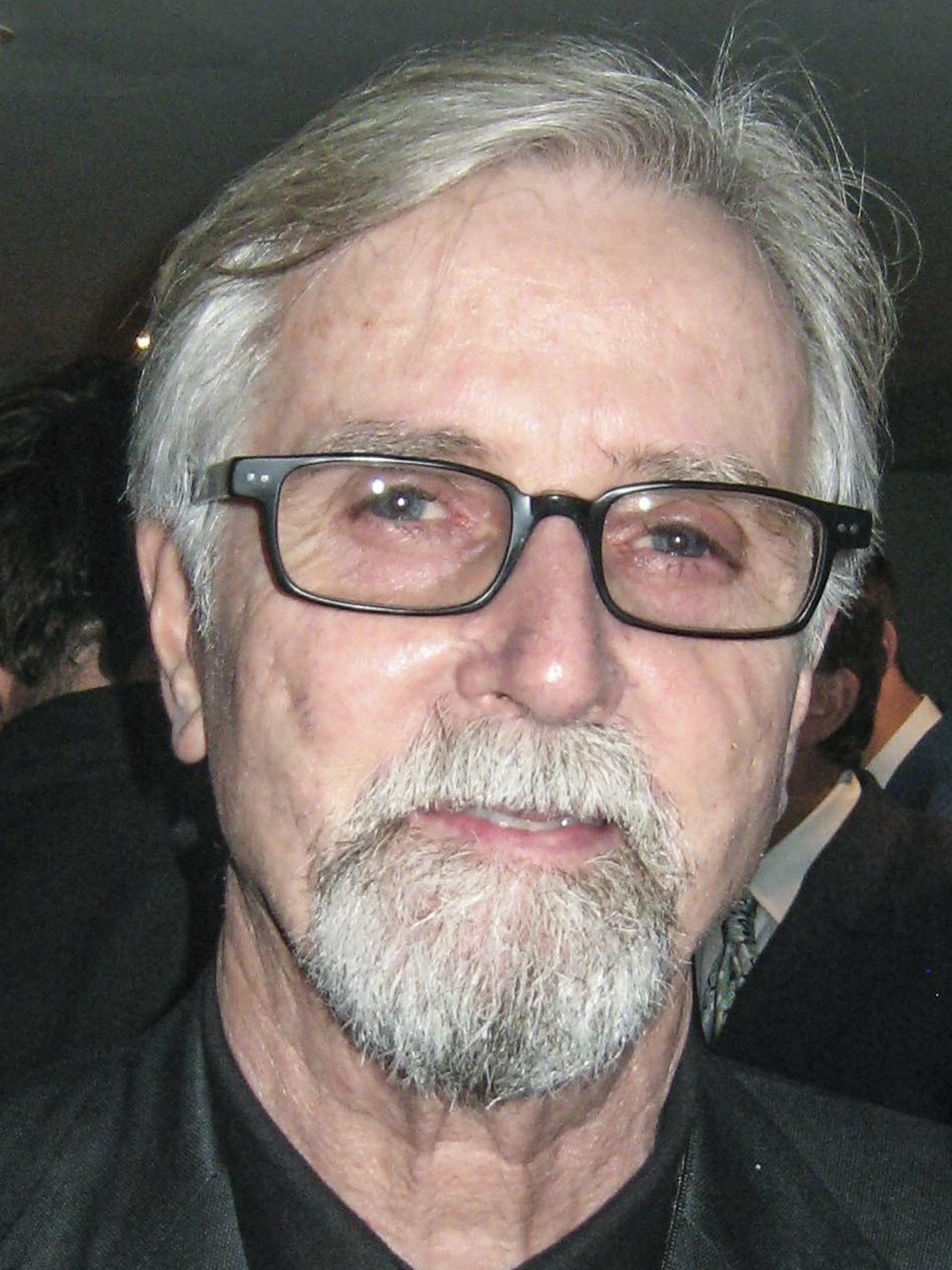

Franc Roddam

director of

Quadrophenia

Talks To Phacemag On its 40th Anniversary

Introduction and I get to play my fav clip...pauliepaul

Quadropohenia the film that put a 'Q' into Classic British film titles will be 40 years old in a few months. Everything that needs to be said about the film has probably already been said. Until now! Eoghan Lyng talks to Franc Roddam the films director in what is a very special interview! - Eoghan is straight in!

Below is one of my favourite scenes, I can't tell you how many times I've laughed when Phil Daniels says "Stitching me up anall, The Bloke!"

Below is one of my favourite scenes, I can't tell you how many times I've laughed when Phil Daniels says "Stitching me up anall, The Bloke!"

Franc Roddam

Talks to Eoghan Lyng

E.Lyng

@wordpress

E.Lyng

@wordpress

Dummy, a naturalistic drama palatable through Italia Grand Prix accoladr, preceded Quadrophenia. How did this influence your journey?

The thing is, Eoghan, I worked in television, working on documentaries. I had directed Dummy, which was incredibly successful. I think 14 million people watched it. So when they were looking for a director, The Who were putting a film together, I was recommended. Alan Parker recommended me to the producers, he’d watched Dummy. Alan, of course, directed The Commitments years later, which Ian Le Frenais and Dick Clement wrote. I worked with them on Auf Wiedershen, Pet. Lovely men.

Ken Russell’s faux fantasia in opulence and grandiosity, is a very different beast to yours. Were you eager to make a film distinct from Tommy?

I did for two reasons. 1) Ken had already made that film.2) I wanted it to be authentic. I went for reality, Ken went for hyperreality {chuckles}. He had strings and opera and I didn’t want any of that. I wanted there to be rock music, not just The Who’s. I was looking at the street movement, it was very real to me. The main character is eighteen in 1964, I was eighteen in 1964. I had a very clear vision for the film which I presented at the beginning. The Who were very gracious in letting me with my vision.

Pete Townshend’s crepsecular double album is a synergy of music and motifs representative of The Who. How was he in collaboration with your vision?

He was very sophisticated and said “it’s your movie”. I explained to him the idea I had, he thought I might be doing it like Ken. He was impressed with my vision and then stood aside to let me make the film. I worked with John Entwistle on the music and talked to Roger Daltrey about the clothes. But Pete largely stepped aside, probably because he recognised the space I needed to make the film. He understood the artistic measures. He’d already done it, the album is superb, though we didn’t go with the band member route. The representation seemed a step too far. We did have a sensitive Phil Daniels and some tough guys like Roger, but we were focusing more on the movement and the working class vision. Damon Albarn lives near me, Blur probably weren’t, but, I’ve always thought they were like working class poets. I was working class and wanted that in the work. I gave a talk at the fortieth anniversary dinner recently and said “it started with Pete Townshend, finished with Phil Daniels and I was the fortunate guy in the middle!”

Phil Daniels’ lead is a revelation. Masculine in status, feminine in sartorial selection, vicious in tongue, cerebral in movement. How was he cast?

Interestingly, there’s always people to work with. I had two casting directors. I didn’t want names. We weren’t going to have John Mills play an eighteen year old! Phil had some experience, he’d made Zulu Dawn, but many didn’t. I had it brought down to about a hundred, then eight finalists, so others could be the second gang or be extras. I got to know the subjects. John Lydon did a screen-test, I thought he was very good. He cut his hair and everything. The bond people, the insurance, only saw the anti-Queen man and wouldn’t insure a person they thought wouldn’t come on set! Phil was initially very sick, green tongue from Zulu Dawn, but my casting director told me to go back to him. We did and I realised how fantastic he was. Great serendipity.

The thing is, Eoghan, I worked in television, working on documentaries. I had directed Dummy, which was incredibly successful. I think 14 million people watched it. So when they were looking for a director, The Who were putting a film together, I was recommended. Alan Parker recommended me to the producers, he’d watched Dummy. Alan, of course, directed The Commitments years later, which Ian Le Frenais and Dick Clement wrote. I worked with them on Auf Wiedershen, Pet. Lovely men.

Ken Russell’s faux fantasia in opulence and grandiosity, is a very different beast to yours. Were you eager to make a film distinct from Tommy?

I did for two reasons. 1) Ken had already made that film.2) I wanted it to be authentic. I went for reality, Ken went for hyperreality {chuckles}. He had strings and opera and I didn’t want any of that. I wanted there to be rock music, not just The Who’s. I was looking at the street movement, it was very real to me. The main character is eighteen in 1964, I was eighteen in 1964. I had a very clear vision for the film which I presented at the beginning. The Who were very gracious in letting me with my vision.

Pete Townshend’s crepsecular double album is a synergy of music and motifs representative of The Who. How was he in collaboration with your vision?

He was very sophisticated and said “it’s your movie”. I explained to him the idea I had, he thought I might be doing it like Ken. He was impressed with my vision and then stood aside to let me make the film. I worked with John Entwistle on the music and talked to Roger Daltrey about the clothes. But Pete largely stepped aside, probably because he recognised the space I needed to make the film. He understood the artistic measures. He’d already done it, the album is superb, though we didn’t go with the band member route. The representation seemed a step too far. We did have a sensitive Phil Daniels and some tough guys like Roger, but we were focusing more on the movement and the working class vision. Damon Albarn lives near me, Blur probably weren’t, but, I’ve always thought they were like working class poets. I was working class and wanted that in the work. I gave a talk at the fortieth anniversary dinner recently and said “it started with Pete Townshend, finished with Phil Daniels and I was the fortunate guy in the middle!”

Phil Daniels’ lead is a revelation. Masculine in status, feminine in sartorial selection, vicious in tongue, cerebral in movement. How was he cast?

Interestingly, there’s always people to work with. I had two casting directors. I didn’t want names. We weren’t going to have John Mills play an eighteen year old! Phil had some experience, he’d made Zulu Dawn, but many didn’t. I had it brought down to about a hundred, then eight finalists, so others could be the second gang or be extras. I got to know the subjects. John Lydon did a screen-test, I thought he was very good. He cut his hair and everything. The bond people, the insurance, only saw the anti-Queen man and wouldn’t insure a person they thought wouldn’t come on set! Phil was initially very sick, green tongue from Zulu Dawn, but my casting director told me to go back to him. We did and I realised how fantastic he was. Great serendipity.

E.Lyng

@CultureSonar

E.Lyng

@CultureSonar

The film features the impossibly handsome Sting. Did his rise in The Police catapult the film into greater fandom?

Funny story, he hadn’t released anything while filming and asked for a day off to do The Old Grey Whistle Test! That was a show back then. He’d had a record when the film came out and piggy backed that off the film. [chuckles] I like Sting. People seem to think he’s up himself, but he isn’t. He’s a great musician and a phenomenal lyricist. A very nice person.

You’ve prescribed the term “method director” on yourself. Would you care to elaborate?

Any method actor will tell you, the method and subect matter is transformative. It’s part of the process. I throw myself into everything I do, I’m never just a technician. I got to know the subjects and went part of the journey with them. I grew to know the cast and talked to them about their characters. It was immensely transformative for all of us, everyone on the set. I was transformed during it and so was Martin Spellman, who helped to write the film.

The sprawling Brighton fight scenes excite in latent bloodied beach violence. How did you achieve this?

Filmmaking has changed over the years. Now there’s much more CGI and Bluescreen. Storyboards are used much more. The way we’d do it, we’d have the locations and the cast and often see what would happen on the day. We’d figure out the shots there. For the Brighton scenes, we had to choreograph it. The chief police man said it was very clever the way we closed off the roads. I had to ask the art director for a map of the place. Film was transitioning from the corny, it used to be that when someone was punched, they’d trampoline. I had to mix it up, gave the actor half a beat notice, so the energy is chaotic and angry. People said I’d made a celebration of sex and violence, but I see it as a celebration of youthful energy. This is a price of youthful energy.

As well as celebrating forty years of Quadrophenia, it’s been twenty years since you directed Timothy Dalton in Cleopatra. How did these projects differ?

I’ve directed two American mini series, Moby Dick and Cleopatra. Both very enjoyable experiences. They weren’t personal projects like Dummy or Quadrophenia, but took my expertise. I’d known Tim from seeing him in L.A. where he lived. Then he came to the set and delivered the performance. I can say he’s a lifelong friend. A very underrated actor, by far the most memorable James Bond. I don’t know why he’s not cast as a Dumbledore or a Lord of The rings type, he has such gravitas! I spoke to him recently and he told me he’s playing an explorer at seventy two. He has great in Penny Dreadful and I hope he gets more recognition as an actor.

From your prerogative, why do you think Quadrophenia is stapled as a British classic?

Every young generation goes to it, probably because of the angst. There’s teenage angst and then there’s authenticity going on through. Phil’s Jimmy isn’t very good at sex, not great at dressing himself, falls out with work and parents. Most films used to be about success, whereas we’re mostly failing in our daily lives in one way or another. There’s something re-assuring about the film as it says “we’re not so bad after all!”

Franc Roddam thanks very much.

Funny story, he hadn’t released anything while filming and asked for a day off to do The Old Grey Whistle Test! That was a show back then. He’d had a record when the film came out and piggy backed that off the film. [chuckles] I like Sting. People seem to think he’s up himself, but he isn’t. He’s a great musician and a phenomenal lyricist. A very nice person.

You’ve prescribed the term “method director” on yourself. Would you care to elaborate?

Any method actor will tell you, the method and subect matter is transformative. It’s part of the process. I throw myself into everything I do, I’m never just a technician. I got to know the subjects and went part of the journey with them. I grew to know the cast and talked to them about their characters. It was immensely transformative for all of us, everyone on the set. I was transformed during it and so was Martin Spellman, who helped to write the film.

The sprawling Brighton fight scenes excite in latent bloodied beach violence. How did you achieve this?

Filmmaking has changed over the years. Now there’s much more CGI and Bluescreen. Storyboards are used much more. The way we’d do it, we’d have the locations and the cast and often see what would happen on the day. We’d figure out the shots there. For the Brighton scenes, we had to choreograph it. The chief police man said it was very clever the way we closed off the roads. I had to ask the art director for a map of the place. Film was transitioning from the corny, it used to be that when someone was punched, they’d trampoline. I had to mix it up, gave the actor half a beat notice, so the energy is chaotic and angry. People said I’d made a celebration of sex and violence, but I see it as a celebration of youthful energy. This is a price of youthful energy.

As well as celebrating forty years of Quadrophenia, it’s been twenty years since you directed Timothy Dalton in Cleopatra. How did these projects differ?

I’ve directed two American mini series, Moby Dick and Cleopatra. Both very enjoyable experiences. They weren’t personal projects like Dummy or Quadrophenia, but took my expertise. I’d known Tim from seeing him in L.A. where he lived. Then he came to the set and delivered the performance. I can say he’s a lifelong friend. A very underrated actor, by far the most memorable James Bond. I don’t know why he’s not cast as a Dumbledore or a Lord of The rings type, he has such gravitas! I spoke to him recently and he told me he’s playing an explorer at seventy two. He has great in Penny Dreadful and I hope he gets more recognition as an actor.

From your prerogative, why do you think Quadrophenia is stapled as a British classic?

Every young generation goes to it, probably because of the angst. There’s teenage angst and then there’s authenticity going on through. Phil’s Jimmy isn’t very good at sex, not great at dressing himself, falls out with work and parents. Most films used to be about success, whereas we’re mostly failing in our daily lives in one way or another. There’s something re-assuring about the film as it says “we’re not so bad after all!”

Franc Roddam thanks very much.

Eoghan Lyng